When we conjure images of the Underground Railroad, we’re mostly likely seeing dimly lit trails in the woods, tight hidden spaces to hide during the day, and the terrifying prospect of being recaptured. What began as an effort by abolitionists to protest slavery in the South became one of the most intricate and successful rebukes of slavery in history. Here, we will investigate the incredible true stories to discover what made the Underground Railroad such a pivotal moment in American history.

The Movement Gathers Momentum

In 1786, George Washington famously remarked that one of his runaway slaves was helped by a “society of Quakers.” These Quakers, also known as members of the Religious Society of Friends, were considered the first abolitionists, and they assisted several of the slaves on Washington’s plantation to freedom in the North. To aid in this process, Quaker leader Isaac T. Hopper formed a network of routes and shelters through Philadelphia to help the runaway slaves. Meanwhile, Quakers in North Carolina began forming their own set of tunnels, and the first sections of the Underground Railroad started to take shape.

The Underground Railroad wasn’t officially called the ‘Underground Railroad’ until 1831, and by then escapes were well underway. By the early 1800s, every northern state had passed laws making slavery illegal. There was such widespread northern support for aiding runaway slaves that it was common to see bake sales and donation sites scattered across cities in the North, where all the proceeds went to those who were assisting the Railroad.

However, this support of abolishing slavery loudly opposed slave owners in the South. Tensions between the North and South grew as conflicting laws were passed by both sides. In 1793, southern state officials were able to pass the Fugitive Slave Act through Congress, which federally permitted slave owners to travel northward and capture runaway slaves to force them back to the South. This law also allowed for the capture of African Americans suspected of escaping slavery in the North, bring them back to the South and, in most cases, receive a hefty financial reward. In response, northern states passed a series of “personal liberty” acts throughout the 1850s, which disputed the Fugitive Slave Acts, and allowed northerners to help runaway slaves. Many northern politicians also openly disputed the runaway slave laws, and encouraged the Underground Railroad’s continuation.

Despite these laws, thousands of slaves were using the Underground Railroad by the 1830s and 1840s. By 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act was expanded, making it illegal for free people to harbor runaway slaves. A guilty charge could result in six months prison time, or a $1,000 fine, a fine equal to nearly $30,000 today. Even with these threats, between 1800 and 1850, an estimated 100,000 slaves escaped, with the help of Vigilance Committees to the North. Most went to major cities in the North, but some went on to Canada, or traveled to the western United States, Mexico, the Caribbean Islands, and South America.

There is a common misconception that the Underground Railroad was a series of underground tunnels or discrete railroads. While this was true in some areas, the system was in general much looser than that. There was no official structure or leader – a characteristic that led to the development of a language of codes that only few trusted individuals associated with the Railroad knew. People who guided runaways were known as “conductors,” locations where slaves could hide were “stations” or “safe houses,” slaves in the safe keeping of their conductor were called “cargo,” and those who hid slaves on their properties were known as “station masters.” The Big Digger, with its handle pointing north, served as a reference point for direction and came to be known as the “drinking gourd.” Likewise, the Ohio River adopted a name from the bible: The River Jordan.

Conducting the Underground Railroad

For most slaves who desired to escape simply getting off their plantation proved to be the most difficult and often most dangerous. Sometimes a “conductor” dressed as a slave would enter the plantation to sneak the runaways out, and lead them northward. Escapees would travel in the night, and had to cover anywhere from 10 to 20 miles between rest stops. During the day, they paused at a “station” to sleep and eat before setting out again after sunset. Occasionally, they would travel by train or boat, though this often cost much more money than most runaway slaves possessed. Money was also needed to improve the appearance of runaways – men, women, and children in tattered clothing would draw suspicion. A “conductor” would normally aid with this too.

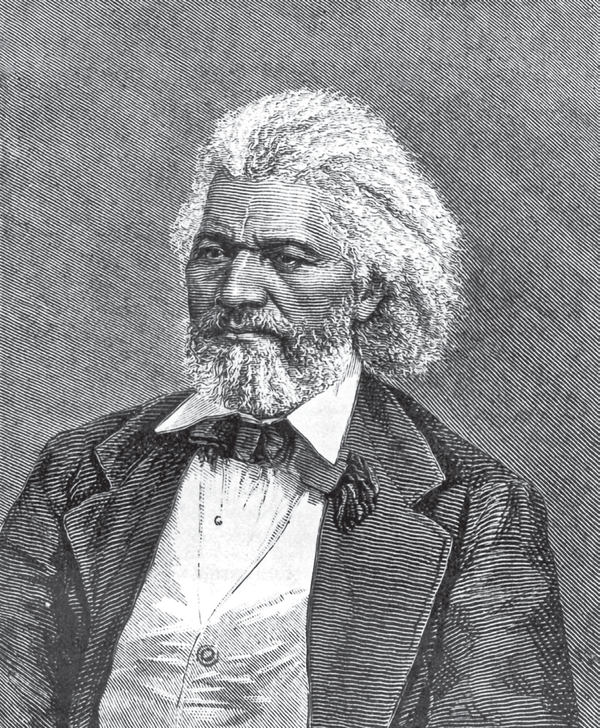

There were over 3,200 people who were known to have worked on the railroad. Harriet Tubman is one of the most famous, as she made 19 individual trips to the South during the 1850s and helped 300 slaves to freedom. Tubman was born a slave, and first got involved in the Railroad to help her family escape. Other people like Levi Coffin, a Quaker, helped more than 3,000 slaves to freedom, and John Fairfield, son of slave owners, made several daring rescues himself. Using his home in New York, Frederick Douglass helped more than 400 escaped slaves reach safety in Canada. Douglass was a former slave himself, and would later become one of the most prominent voices in promoting the abolishment of slavery throughout the 1800s.

Due to the Civil War in 1863, the Underground Railroad stopped. It’s estimated that 179,000 free African American men served in the Civil War, making up 10% of the Union Army. Today, we remember the Underground Railroad as an incredible feat, conducted by average famers and business owners, and a handful of courageous individuals who repeatedly risked their lives making trips southward. The Underground Railroad marks a strained time in American history, but the hope and determination of those involved will be remembered for years to come.