Despite the development of entertainment forms like cinema, television, and radio, theatre has remained a prominent part of the American entertainment industry. With creations like Vaudeville, American theatre has consistently reinvented itself to remain relevant within the modern entertainment landscape.

The Roots of American Theatre

The history of American theatre begins in the colonial era, long before the United States was a formed nation. Bringing a repertoire from England that included productions like Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Othello, the first American playhouse was started on the Palace Green in Williamsburg, Virginia by merchant William Levingston in 1716. This theatre was closely followed by the opening of the Dock Street Theatre in Charleston, South Carolina in 1730.

However, theatre in the New World struggled during the 18th century as a result of several factors. Tensions between the colonies and Britain increased, and concerns over the moral implications of both acting in and viewing plays arose. In colonies like Massachusetts or Pennsylvania, laws were passed to forbid the production and performance of plays.

This opinion was supported by many prominent philosophers and even the governing bodies of the era. Prior to the penning of the Declaration of Independence, the first Continental Congress passed the Articles of Association, a document written in response to the British Intolerable Acts. The Articles in part called for a “discountenance and discourage [of] every species of extravagance and dissipation, especially… exhibitions of shows, plays, and other expensive diversions.” As British rule and culture were increasingly criticized in the colonies, tenets of British society such as theatre came to be almost abhorred in the colonies, who attempted to distance themselves from their rulers. As a result, theatre was denounced in the same vein as vices like gambling and animal fighting.

Theatre was also religiously discouraged, as major sects of colonial religion (including the Puritans and Quakers) had protested against the development of theatre since the 17th century. These religions believed that theatre could present a danger to the “immortal soul,” and opposed the Christian God. George Fox, the founder of the Quaker faith, went as far as to say he believed music and the stage “burthened the pure life, and stirred up the people’s vanity,” implying that he believed theatre made it impossible for people to lead a “pure” life in pursuit of God.

As a result of these challenges, theatre struggled to gain a true foothold in American culture until the 1800s, when fears over the morality of plays began to subside. That isn’t to say that the American population immediately welcomed actors and playhouses with open arms – early 19th century actors were often viewed as little more than common prostitutes, and while audiences enjoyed productions, acting was not considered a respectable career. It was not until the mid-19th century that actors began to be respected within society, but at this point influential persons (such as authors or politicians) began to receive and entertain actors, indicating their newly-elevated social status.

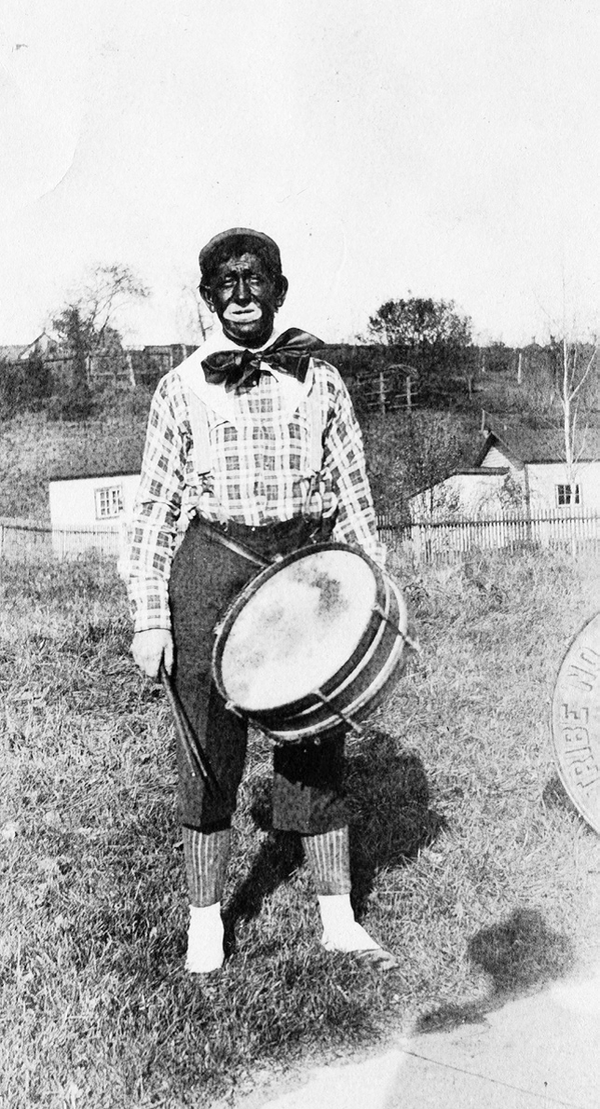

Types of productions during this time period varied widely. While there was some development of a purely “American” theatre, with plays like “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and “The Octoroon; or, Life in Louisiana written by early American playwrights, minstrel shows dominated as a the popular entertainment form. Minstrel shows, which consisted of skits which mocked people of African descent, were primarily performed by white actors in blackface. The shows date back to the 1830s, but continued until the early 20th century, with the last professional minstrel shows being performed near 1910. While minstrel shows continued in informal settings past the 1910s, they fell into disfavor as the Civil Rights Movement began to gain traction during the mid-20th century, and had mostly ceased by the 1950s.

Vaudeville and Pre-World War II Theatre

By the 20th century, minstrel shows had mostly fallen to the wayside in favor of vaudeville. Vaudeville productions consisted of multiple unrelated acts grouped together on the same playbill, and began rising in popularity during the 1880s. By the 1900s, Vaudeville performances included anything from trained animals to one-act plays and magicians. Many celebrities of the era got their start on the Vaudeville stage, including comedians Abbot and Costello, singer Judy Garland, and novelty act Harry Houdini, amongst others.

Vaudeville performances continued well into the 1930s, and remained popular until the advent of World War II. Even after the last of the Vaudeville stages had cleared, however, the influence of the art form could be felt in early film, radio, and TV – film and TV comedies frequently adopted comedic Vaudeville tropes, like “using the hook” to clear out a bad act. Some Vaudeville actors eventually made the transition from stage to cinema (like Judy Garland), although others simply retired. In addition, Vaudeville helped to directly inspire the variety shows of the 1950s and 60s, such as The Ed Sullivan Show and The Sonny & Cher Comedy Hour.

Traditional theatre also rose in prominence and distinction between 1900 and World War II, and theatre personalities attained a status similar to modern movie stars in what was an early form of the Hollywood celebrity. Families of actors such as the Barrymores dominated the theatre scene (and have continued to dominate in film). In addition, traditional theatre gained the support of the US government with President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Federal Theatre Project, which ran from 1935 – 1939. The project, which aimed to provide jobs to actors, writers, and directors who had been unemployed due to the Great Depression, successfully produced 830 major titles during its four years of operation, and employed over 12,000 people.

However, the success of theatre came into question with the development of sound cinema throughout the 1920s and 30s. As cinema became a more popular form of entertainment, live stars began to struggle to make a living, unable to compete with their cheaper-price silver screen counterparts. As a result, while Vaudeville performers and comedians largely did not survive the transition to cinema (unless they were to join cinema themselves), somewhat less common forms of the stage came to the forefront, particularly musical theatre. Productions like Show Boat and Anything Goes became increasingly popular, and by the 1940s musical theatre had entered a so-called Golden Age, with composers like Gershwin and Rodgers & Hammerstein dominating the stage.

Post World War II and Modern Theatre

The decades following World War II saw the true international fame of American theatre. Productions like The Crucible by Arthur Miller in 1953 and A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams in 1947 became international sensations, and Williams’ play was produced on the London stage by 1949. Musical theatre also maintained its popularity following WWII, and developed along with traditional theatre into more daring productions during the 50s and 60s.

As modern society began to develop, musical and dramatic theatre progressed into “agenda” theatre, particularly during the Civil Rights Movement. This type of theatre attempted to address the social justice issues of the era, and musical productions such as Hair and West Side Story referenced subjects such as drug culture, racism, and cultural divides. As a result, drama has historically become a way for playwrights to address social rights issues, personal experiences, and pass their own judgment on society.

While cinema had presented a large challenge, theatre struggled more-so to compete against the rise of radio and television. Once again facing competitors that were much cheaper than traditional shows, the struggle of the theatre was compounded by the admissions tax, a tax only applied to businesses which charged an admissions fee to patrons (such as amusement parks, athletic events, or the theatre). While the admissions tax was implemented in 1918, it was doubled in 1943. As a result, the combination of taxes and a declining number of patrons have made it difficult for playhouses to turn a profit even in the modern day.

To combat the loss of revenue experienced during the mid-20th century, theatre at the turn of the 21st century began to borrow heavily from cinema and literature – productions like Disney’s The Lion King have been massively successful nationwide, and have led to other films being adapted to the stage, such as Disney’s Aladdin, Mary Poppins, and Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein. In addition, literature has helped to inspire composers, such as Andrew Lloyd Webber’s renowned The Phantom of the Opera, which is currently the longest running show in Broadway history since premiering in 1986.

Today, Broadway productions have built on the success and revitalization of both agenda theatre and cinema-based musicals, with productions becoming more elaborate and expensive. Popular modern musicals, such as Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton and Stephen Schwartz’s Wicked have proven successful with modern audiences, while dramatic productions such as Tony Kushner’s Angels in America continue to address social justice concerns. In a country that has endured major periods of transformation in its relatively short existence, American theatre has remained a popular form of expression due to its ability to adjust to changing times and trends – a fluid industry that adjusts to the social setting it finds itself within.